![]()

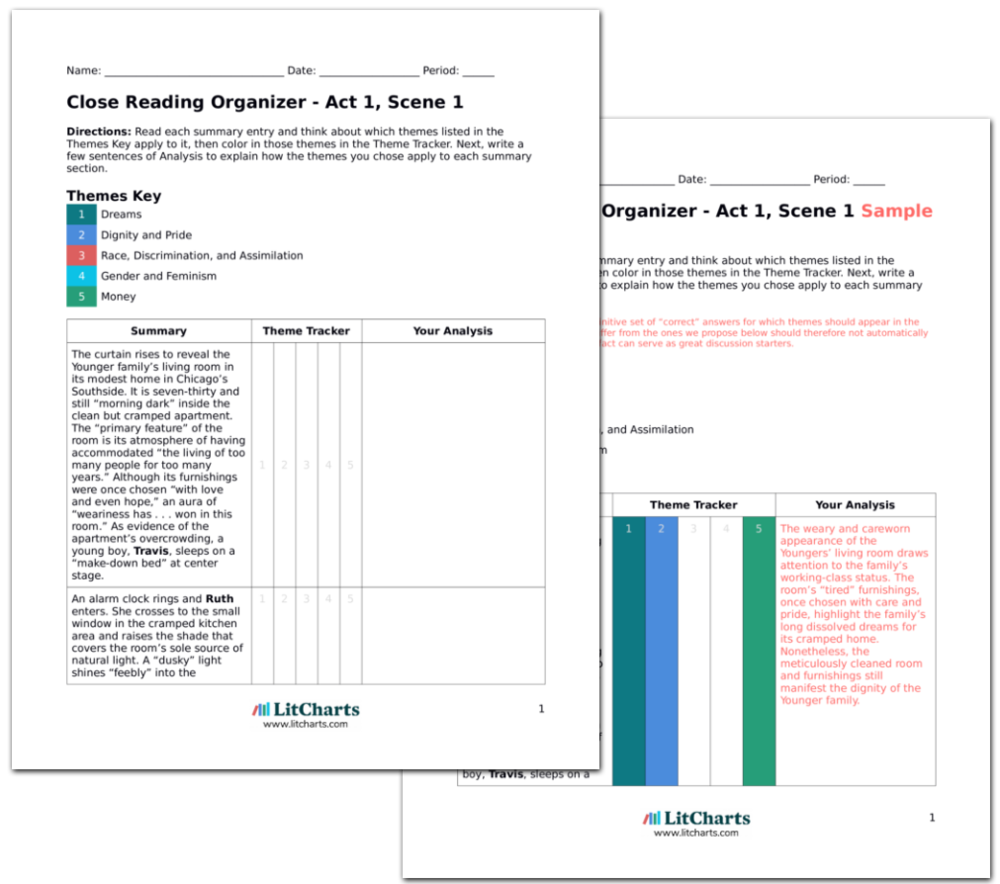

LitCharts assigns a color and icon to each theme in A Raisin in the Sun, which you can use to track the themes throughout the work.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The curtain rises to reveal the Younger family’s living room in its modest home in Chicago’s Southside. It is seven-thirty and still “morning dark” inside the clean but cramped apartment. The “primary feature” of the room is its atmosphere of having accommodated “the living of too many people for too many years.” Although its furnishings were once chosen “with love and even hope,” an aura of “weariness has . . . won in this room.” As evidence of the apartment’s overcrowding, a young boy, Travis , sleeps on a “make-down bed” at center stage.

The weary and careworn appearance of the Youngers’ living room draws attention to the family’s working-class status. The room’s “tired” furnishings, once chosen with care and pride, highlight the family’s long dissolved dreams for its cramped home. Nonetheless, the meticulously cleaned room and furnishings still manifest the dignity of the Younger family.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

An alarm clock rings and Ruth enters. She crosses to the small window in the cramped kitchen area and raises the shade that covers the room’s sole source of natural light. A “dusky” light shines “feebly” into the apartment, and while Ruth begins preparing breakfast, she calls to her son Travis to wake up. After her calls are ignored, Ruth goes over to Travis and finally shakes him out of bed, sending him off to the hallway bathroom before one of the neighbor’s can occupy it.

As the first of the Youngers to wake up in the morning, Ruth assumes the duties of a traditional mother, preparing meals for her family and helping her son get ready for school. The shared hallway bathroom offers another example of the Youngers’ modest financial situation.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

Ruth’s husband Walter Lee enters from the bedroom, and almost immediately he mentions the “check” that the family is expecting the next day. Ruth answers impatiently that it’s too early to start discussing money, which sparks tension with her husband. While Ruth prepares breakfast, the couple continues bickering over yesterday’s late-night gathering that Walter held for his friends in his son’s makeshift “bedroom.” Walter dismisses his wife’s complaints by saying that “colored [women] . . . [is] some eeeevil people at eight o’clock in the morning.”

Walter’s immediate reference to the coming “check” emphasizes the family’s preoccupation with money. Ruth’s complaints about her son’s makeshift bedroom also relate directly to the family’s strained finances. Walter’s comment on “colored” women speaks to his own insecurities regarding his shaky sense of manhood and also hints at the ways that hardship can make people blame each other.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

Travis returns from the bathroom and signals for his father to get inside before one of the neighbors beats him to it. Travis begins eating his breakfast and, like Walter , also asks his mother about the check that is scheduled to arrive tomorrow. Travis reminds his mother that he is supposed to bring 50 cents to school this morning, to which Ruth answers that she “ain’t got no fifty cents” today. Travis persists in asking for the money and, exasperated, Ruth refuses and tells her son to be quiet. Angered by his mother’s resistance, Travis heads for the door, but before he can leave for school, Ruth gently teases him and asks for a good-bye kiss. Travis’ frustration fades, and mother and son embrace and reconcile.

Travis’ mention of the anticipated check shows that the family’s financial concerns extend to its youngest member. Travis finds his mother’s refusal to give him the 50 cents that he needs for school extremely frustrating and embarrassing, since it means that he will have to reveal his family’s economic struggles to his teacher and classmates. Nonetheless, familial love reconciles mother and son after financial strain divides them.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

"My students can't get enough of your charts and their results have gone through the roof." -Graham S.

Walter reenters and, hearing the tail end of the argument between his wife and son, gives Travis a dollar to take to school, which greatly angers Ruth . Walter’s defiance of Ruth’s decision provokes further conflict between husband and wife. In particular, Ruth criticizes Walter’s friend Willy Harris and his business schemes, the latest being a liquor store that Harris has asked Walter to invest in. Walter asks Ruth to try to persuade his mother, Lena , to use part of the coming check to invest in the store. Ruth resists the idea and tells Walter to “eat your eggs.” In response, Walter erupts, accusing his wife of hampering his dreams. Ruth “wearily” explains her indifference by telling Walter that he simply “never say nothing new.” Walter retorts, saying that “colored women . . . don’t understand about building their men up.”

Unable to stomach the loss of pride that would come with the denial of his son’s request, Walter shortsightedly gives Travis more money than the family can spare. Fixated on the dream of providing a stable financial future for his family, Walter begs his wife to support him in his ambition to open a liquor store. When Ruth expresses doubts about the security of such an investment, Walter lashes out with criticism of African-American women in general, redirecting his own anxieties towards his wife and blaming her for his failings as a male provider.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Walter’s sister Beneatha enters from the stage-left bedroom in the midst of Walter and Ruth’s quarrel. As Ruth irons a massive pile of clothes, Walter badgers his sister about her decision to study medicine and the high cost of her schooling. Beneatha counters sharply and impatiently, and when Walter brings up the coming check, Beneatha quickly and decisively reminds Walter, “That money belongs to Mama .” Walter “bitterly” snaps back, pointing to Beneatha’s own hope that Mama will devote a portion of the check to her tuition. Walter tells Beneatha to “stop acting holy” and acknowledge the “sacrifices” that he and the rest of the family have made so that Beneatha can go to school. Beneatha, in a semi-mocking tone of gratitude, drops to her knees and cries, “Forgive me for ever wanting to be anything at all!”

Walter’s critique of his sister’s dream highlights his traditional view of gender roles, which Beneatha and her professional ambition challenge. The issue of money, embodied by the check, again serves as a point of conflict for the family members. Walter laments the high cost of Beneatha’s tuition, which would divert money away from his dream of opening a liquor store. Beneatha’s tongue-in-cheek apology for “ever wanting to be anything at all” underlines her pride in her dream and her dismissal of the expectation that women should give up their own dreams and instead just support men.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Walter goes on to suggest that his sister abandon her dream of becoming a doctor in favor of being “a nurse like other women,” or simply getting married. Beneatha responds by telling Walter, “Thee is mad, boy.” Following his argument with Beneatha, Walter “slams out of the house” on his way to work. However, a few moments later, Walter reenters, fumbling with his hat, and tells Ruth that he needs “some money for carfare,” having given his last cent to Travis earlier. Ruth gives the money to her husband and in a “teasing, but tenderly” manner says, “Here, take a taxi!”

Walter’s attempt to convince his sister to sideline her dream reflects his uncompromising stance on gender and his determination to secure Mama’s money in order to fund his own dream. Walter’s re-entrance to ask for carfare recalls his imprudent decision to give Travis his money—foreshadowing future poor decision-making around money—and Ruth’s reaction shows that she facilitates Walter’s irresponsibility with money.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Mama enters from her bedroom and asks Beneatha and Ruth about the argument with Walter that she just overheard. When Beneatha exits to go to the bathroom, Ruth reveals that the siblings’ argument had to do with “that money” that’s arriving in tomorrow’s check. Ruth asks Mama if she has decided what to do with the money and encourages her to consider investing in Walter’s liquor store venture, adding that African Americans need to “start gambling” on such ventures if they want to get ahead in life. Mama dismisses the idea, stating, “We ain’t no business people.” Mama asks Ruth about her sudden support for Walter’s investment scheme, to which Ruth answers that “something is happening” between the couple and that Walter “needs this chance” to restore his self-esteem and repair the rift in their marriage.

In a drastic change from her earlier conversation with Walter, Ruth tries to convince her mother-in-law to use the money from the check in order to fund Walter’s dream, hoping that the fulfillment of her husband’s ambition will give him the confidence boost needed to fix their marriage. Mama’s response – “We ain’t no business people” – takes on a racial dimension in contrast to Ruth’s statement that African Americans need to start taking chances in business in order to better their standing in society.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Studying Ruth’s tired face, Mama suggests that Ruth call in sick to work today, an idea that Ruth swiftly refuses, stating that the family “need[s] the money.” With the mention of money, the conversation promptly circles back to the anticipated check, which Mama reveals is a $10,000 insurance payment resulting from her husband’s recent death. Mama declares that some of the money must be set aside for Beneatha’s schooling. As for the remaining amount, Mama “tentatively” begins to tell Ruth of her and her late husband Big Walter’s deferred dream of buying a house. Mama suggests that she might use part of the insurance money as a down payment on a “little old two-story somewhere, with a yard where Travis could play.”

Big Walter’s insurance policy represents the interconnectedness of the play’s themes of money, dignity, and dreams. The cost of acquiring and maintaining the $10,000 policy during Big Walter’s life would have placed a considerable financial burden on the man, although the policy now makes possible the fulfillment of at least some of his family’s dreams. Through his death, Big Walter continues to provide for his family and helps to reinforce its sense of dignity and pride.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

In a “reflective mood,” Mama smiles and reminisces about her marriage, stating that she and Big Walter only intended to stay in their current apartment for “no more than a year.” Growing sad at her “dissolved dream,” Mama recalls the loss of her baby Claude and the difficulties of her marriage, including Big Walter’s “wild” way with women. Mama states that, for all his faults, her husband “sure loved his children,” and he often said, “Seem like God didn’t see fit to give the black man nothing but dreams – but He did give us children to make them dreams seem worth while.”

Mama betrays herself as a member of an older generation with different thoughts on marriage when she reveals that she tolerated her late husband’s womanizing. Mama’s remembrance of Big Walter’s statement about the chronic deferment of the “black man[‘s]” dreams draws attention to the widespread racial inequalities and prejudices in America that limited African Americans’ employment, educational, and housing opportunities.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

Beneatha returns from the bathroom and angers Mama by “reciting the scriptures in vain” when she exclaims “Christ’s sakes” in response to a neighbor’s noisy vacuuming. Beneatha then mentions her after-school guitar lesson that evening, which provokes snide comments from Mama and Ruth , who proceed to rattle off the long list of Beneatha’s discarded – and expensive – hobbies. Beneatha defends her experimentation with different hobbies as part of her effort to “express” herself, which prompts “raucous laughter” from Mama and Ruth.

Although Beneatha defends and takes pride in her quest for a form of personal “expression,” Mama and Ruth can’t help but laugh at Beneatha’s youthful effort to define her identity, which represents an unimaginable luxury to these women of earlier, pre-feminist generations. The money devoted to Beneatha’s hobbies underscores the family members’ financial tug-of-war.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

Mama then changes the subject to Beneatha’s love life, asking whom she will go on a date with tomorrow night. “With displeasure,” Beneatha says it will be George Murchison , a “rich” young man whom she condemns as “shallow.” Ruth disagrees with Beneatha’s dismissal of George, asking her, “What other qualities a man got to have” in addition to his wealth? Beneatha resists her sister-in-law’s advice, affirming that she first and foremost intends to become a doctor and only then will she consider whom to marry – that is, “If I ever get married.”

Ruth and Beneatha have a difference of opinion when it comes to the relevance of wealth in choosing a mate; however, Ruth’s own decision to marry the working-class Walter shows that she hasn’t necessarily heeded her own advice. In the face of societal – and familial – pressure to marry, Beneatha prioritizes her independence and freedom over love or the financial security that comes from marriage.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

![]()

After recovering from the shock of Beneatha’s comment, Mama says that Beneatha will certainly fulfill her dream of becoming a doctor, “God willing.” Beneatha chafes at the mention of God, responding that divine will “doesn’t have a thing to do with it.” Beneatha continues, delivering a speech in which she coolly declares, “God is just one idea I don’t accept.” After absorbing the speech, Mama slowly crosses to Beneatha and “powerfully” slaps her, and then with “cool emotion” makes her repeat, “In my mother’s house there is still God.” Beneatha acquiesces and Mama exits. To Ruth , Beneatha calls Mama “a tyrant” before leaving for school.

Beneatha prides herself on the progress that she has made towards achieving her dream of becoming a doctor, which is why she resists Mama’s suggestion that God has a role in the fulfillment of her ambition. On the other hand, Mama takes pride and finds strength in her religious convictions, which she has tried to instill in her children. Mama’s reprimand of Beneatha signifies the pride that she takes in maintaining a certain type of home for her family. The entire exchange shows that Mama is still the leader of this family.

Active Themes![]()

![]()

Mama reenters and expresses her deep concern for her children, telling Ruth , “There’s something come down between me and them that don’t let us understand each other.” Tending to her struggling plant by the apartment’s tiny window, she continues to think aloud and, with her back to Ruth, fails to realize that her daughter-in-law is growing faint. At last Mama turns to find that Ruth has “slipped” to the floor in a faint.

Mama’s unending attention to her struggling houseplant symbolizes the pride that she takes in tending to her fractured family and maintaining its sense of dignity and integrity, despite the rough and suffocating conditions. Ruth’s unexplained fainting ends the scene with a note of tension and uncertainty.

Active Themes![]()

“Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!”

Get the Teacher Edition

“This is absolutely THE best teacher resource I have ever purchased. My students love how organized the handouts are and enjoy tracking the themes as a class.”

Copyright © 2024 All Rights Reserved Save time. Stress less.AI Tools for on-demand study help and teaching prep.

Quote explanations, with page numbers, for over 44,324 quotes.

Quote explanations, with page numbers, for over 44,324 quotes. PDF downloads of all 2,003 LitCharts guides.

PDF downloads of all 2,003 LitCharts guides. Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level. Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level.

Expert analysis to take your reading to the next level. Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.

Advanced search to help you find exactly what you're looking for.